Digital banking for business

Seamlessly access all of your accounts from one place with First Citizens Digital Banking for business.

Nerre Shuriah

JD, LLM, CM&AA, CBEC® | Senior Director of Wealth Planning and Knowledge

When you're ready to retire or want to liquidate a portion of your ownership, you'll have various pathways toward selling some or all of your business. Knowing how you'd like to transition your company can help narrow down your options.

Some owners decide to sell all or a portion of their company to employees as they transfer ownership. In doing so, they help ensure key employees stay by giving them a stake in the business while also retaining the company's culture and vision. For these owners, an employee stock ownership plan, or ESOP, is a solid strategy to consider.

In 2019, 94% of respondents to The ESOP Association's Economic Performance Survey reported that implementing an ESOP was a good decision, with 85% noting that it positively affected culture and 63% reporting that it improved employee productivity.

According to results from a Harvard Business Review survey, companies that instituted ESOPs found that their annual employment growth outstripped that of comparison companies by 5.05%, while sales growth was 5.4% faster. Moreover, 73% of the ESOP companies in the sample significantly improved their performance after establishing their plans.

While ESOPs can have a positive impact on a company, it's important to understand the ins and outs of establishing one—including how they're structured and their potential tax advantages.

ESOPs are tax-qualified defined contribution plans designed to invest primarily in the stock of the sponsoring employer. Because of this, they're subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, or ERISA, which sets standards for certain employer-sponsored retirement plans. It's important to note that ESOPs are exempt from ERISA rules forbidding qualified plans from investing greater than 10% of assets in employer securities.

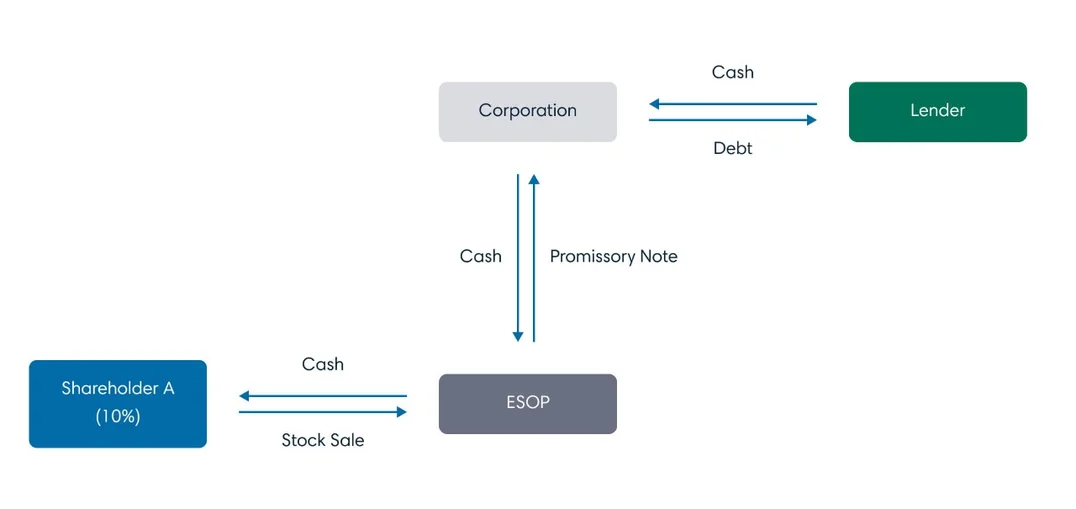

Typically, an ESOP is a leveraged transaction with a trust holding the stock purchased by the ESOP. Employees who receive shares of the stock through an ESOP technically don't hold the shares. Instead, the ESOP trust is the shareholder. Employees are often allocated stock based on compensation, merit, seniority or similar management-by-objective factors.

In a leveraged ESOP, shares are initially held in a suspense account and are then released and allocated to employee accounts in the plan gradually over the term of the ESOP.

Here's an example of how an ESOP may be structured.

There are some requirements to keep in mind when establishing an ESOP.

There are three main tax benefits for businesses and their owners that accompany ESOP transactions.

In a leveraged transaction, both principal and interest payments on the lender loan are deductible to the corporation, subject to Internal Revenue Code Section 415 limits. This is because the initial contribution to the ESOP was a contribution to a qualified plan, and if it doesn't exceed 25% of eligible payroll the entire debt service is deductible to the corporation.

Another benefit is that any portion of an S corporation owned by an ESOP doesn't pay federal corporate income taxes. Under the provisions of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, an ESOP's share of S corporation earnings aren't subject to taxation as unrelated business income tax unless the ESOP runs afoul of certain anti-abuse provisions.

Partially owned S corporations don't pay tax on the pro rata portion of taxes owned by the ESOP. For example, if 35% of the S corporation is owned by an ESOP, then 35% of the corporate income tax bill doesn't need to be paid. Shareholders pay income taxes on profits corresponding to the percent of shares not owned in the ESOP.

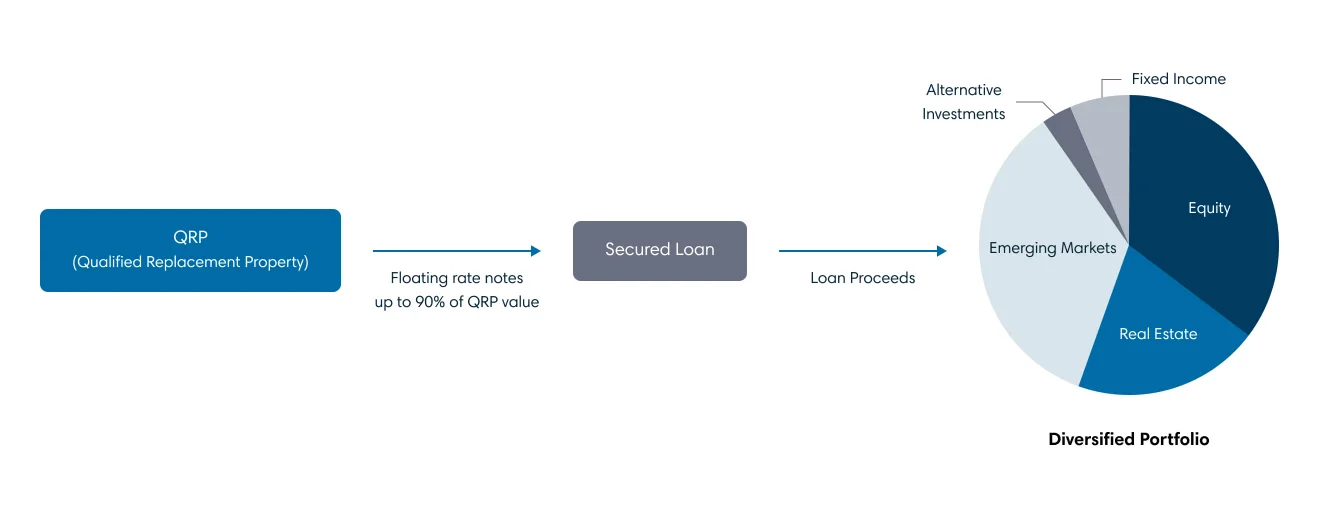

Lastly, if the company is a C corporation, the owner can defer capital gains on the sale of stock by rolling the cost basis into a commensurate investment—in this case, a QRP—within a year. A statement of purchase of a QRP must be filed with that year's tax returns. If the securities are sold, called or mature, then capital gains are due. However, being locked into a portfolio of equities can create risk, so many owners choose to leverage their QRP.

A more detailed definition of a QRP is securities issued by a US corporation that meets the following requirements:

QRP can be stocks, stock rights, debentures, bonds, preferred stocks, warrants, convertible bonds, floating-rate notes, certificates of US companies or other securities. Remember that bonds can be called, triggering a capital gain.

Investments that don't qualify as QRPs include real estate and real estate investment trusts, or REITs, as well as mutual funds, municipal bonds, US government securities, partnership interests, certificates of deposit, securities of foreign companies and securities of a sponsoring corporation.

According to IRS Section 1042, a business owner is only allowed to declare a QRP once. While they can purchase a diversified portfolio with ESOP sale proceeds, they'd need to hold it as a static investment to continue to avoid the capital gains taxes, which could create risks. This is why many owners leverage their QRP with floating-rate notes designed especially for ESOP sales. These are securities with maturities of 30 to 50 years issues by a few lenders with high credit ratings to mitigate risk. The owner would take the proceeds of the sale of shares to an ESOP and invest in a QRP. Up to 75% to 90% of the QRP is then used as collateral against a loan. The loan proceeds are then invested in a diversified portfolio.

In addition to its tax advantages, there are many other benefits of implementing an ESOP.

While ESOPs have significant advantages for flexibility, taxes and business value drivers, there are many steps and requirements that can make it an involved process—and it's not a fit for every business owner. A leveraged ESOP structure can involve up to three separate loans, which involve business risk, and the program itself must comply with ERISA regulations.

Some ESOPs also include seller financing, which involves some risk. If someone sells all of their stock over a series of transactions, it could take up to 7 to 10 years to fully liquidate. And as employees vest and retire or separate from the business, the company must repurchase these shares back from employees, resulting in additional costs.

An ESOP is a strategy that has many advantages for both an owner and a company. It's important to consult with a professional to determine if it's the right approach to transition out of your own business or liquidate your ownership.

Email Us

Please select the option that best matches your needs.

Customers with account-related questions who aren't enrolled in Digital Banking or who would prefer to talk with someone can call us directly.